Three filmmakers.

Three writer/directors who rose to prominence in the 80s and 90s have had an oversized influence on how I understand movie making, more particularly, how accessible filmmaking can be.

As a tween of the 90s, the first should be obvious: Kevin Smith. Smith’s process is the anathema of what was considered the appropriate way to write screenplays and start productions. He didn’t write how people talk naturally, but wrote how he wanted/wished people would speak—the dialogue became a main focus. As an aspiring (and impressionable) writer, I found that validating and inspiring.

The second is Sam Raimi. I cannot stress enough how impressive it is that The Evil Dead and Evil Dead 2 were made, let alone be as good and celebrated as they are. Entire film programs can be taught using these two movies, featuring DIY rigs and in-camera technologies that are still practiced and referenced to this day. They are movies filled with the kind of creativity that’s only possible with a lack of resources and no one telling you what you can’t do. If you ever want to hear the most charming film lectures, listen to the director commentaries on all three Evil Dead movies. It’ll make you fall in love with movie making, even if sloppy horror movies aren’t your speed.

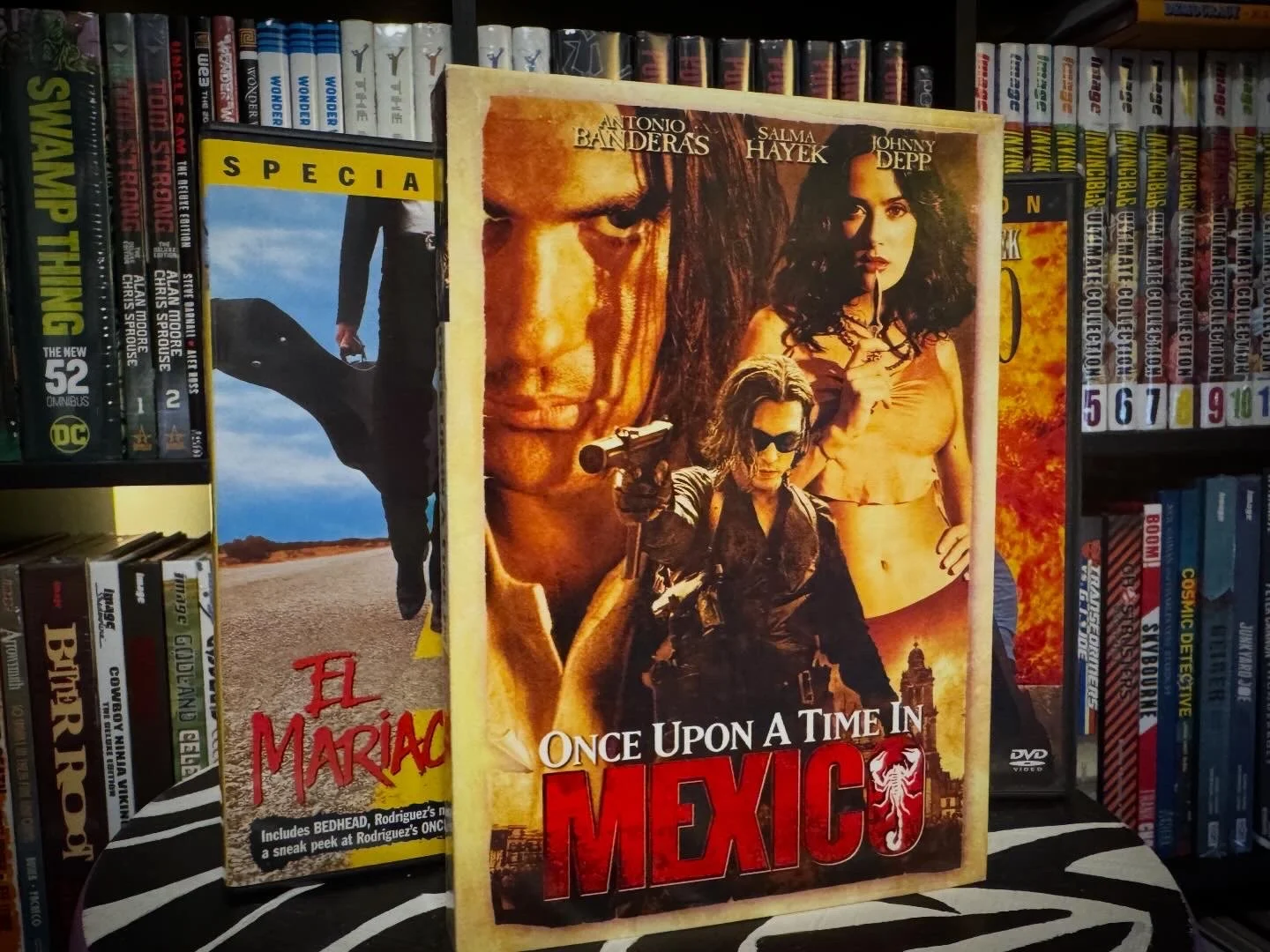

The third, which should be obvious considering the subject of this piece, is Robert Rodriguez. Rodriguez’s big break was with 1992’s El Mariachi —a Spanish language sun-bleached western about a gun-toting mariachi guitarist—made for only $7000 (that doesn’t include the investments he got to complete post-production, which by Hollywood standards is still cheap). The movie went on to gross $2M domestically and set the filmmaker up as a contemporary of Tarantino, Spike Jonze, Soderbergh, and Linklater.

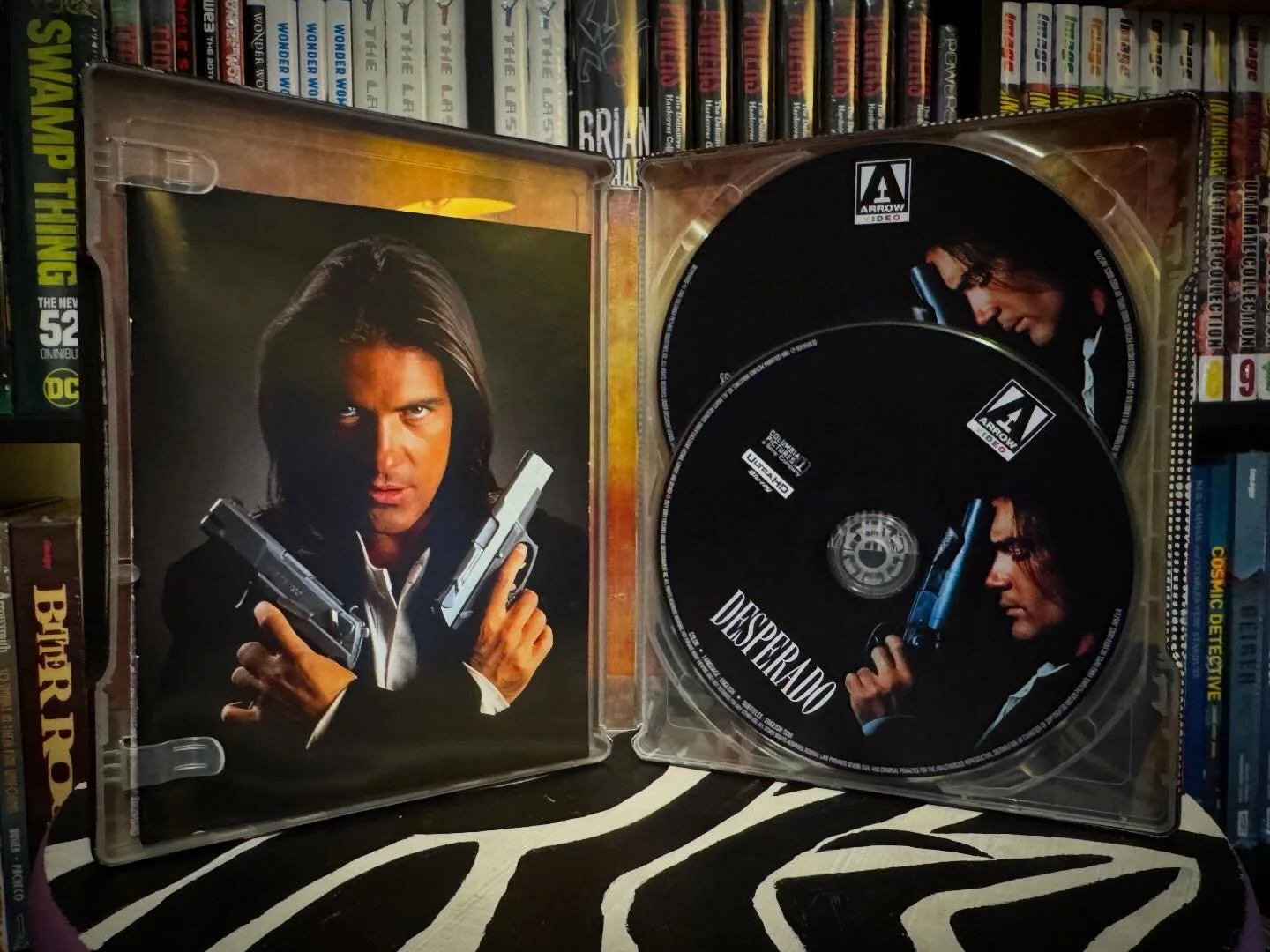

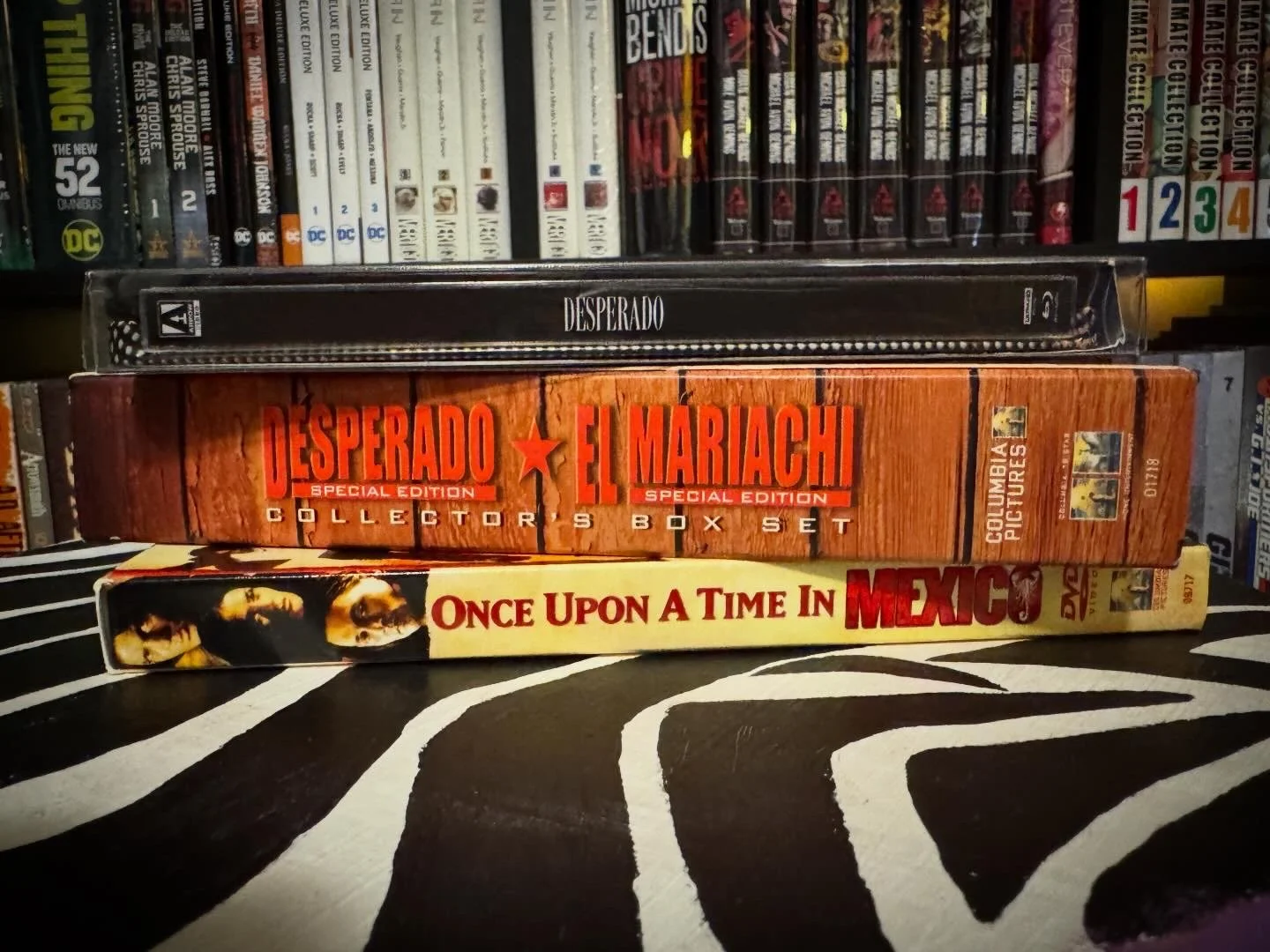

Rodriguez’s 1995 book, Rebel Without A Crew, became an unofficial film school textbook, wherein he would recount stories of ingenuity and necessity, from editing techniques to mimic rapid gunfire to submitting himself into clinical trials so he’d have paid time to write a screenplay, all to get El Mariachi made. It’s a quick and straightforward read about lo-fi filmmaking and I ate it up. In that same year, he released his biggest movie to date—the bigger-budget sequel of his first film, DESPERADO.

DESPERADO is to EL MARIACHI as EVIL DEAD 2 is to THE EVIL DEAD—an exponentially escalating sequel, in both story and production value, that functions independently of its predecessor. Both even contextually recap the events of the previous films in their first acts. The studio basically gave an exciting startup filmmaker more money and said, “do what you did before, but more.” Rodriguez successfully elevated his skillset without sacrificing the story’s representation of Mexican culture.

“[DESPERADO] mythologizes our antagonist before he utters a single word, and when he does open his mouth, it’s to sing.”

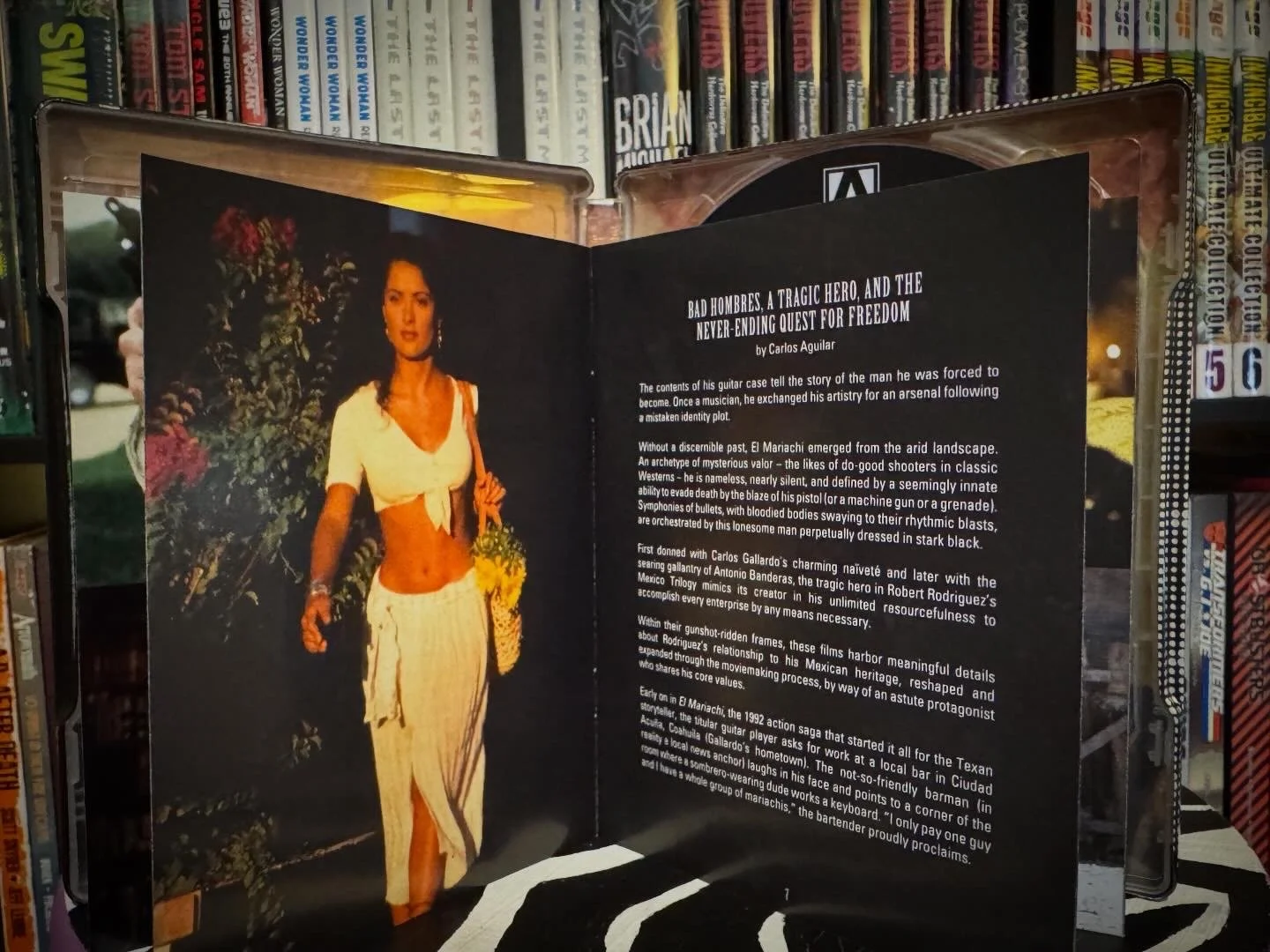

DESPERADO is a western—mysterious and curt stranger with no name (Antonio Banderas) passes through a small town on his single-focused quest for revenge, only to be compelled into action when the townspeople around him (mostly extras and character actors save for Salma Hayek as a no-bullshit bookstore owner) suffer injustice at the hands of an evil drug dealer and his colorful goons. Oh, there’s also a guitar case full of guns.

It’s inventive, ridiculous, break neck, and has one of the more engaging openings of any movie from that era. The first fifteen minutes alone can function as a short film and set up a universe where everything that comes next seems possible—even the things that defy credulity.

DESPERADO, now 30 years old, mythologizes our antagonist before he utters a single word, and when he does open his mouth, it’s to sing. This juxtaposition from many other storytellers would be jarring, but Rodriguez’s confidence behind the camera shines through (as it should—he shoots, edits, and directs himself). He’s not concerned with what might conventionally make sense next, but more so what excites him in every next moment. The director quests to capture a feeling first and then reverse engineers the setting and surroundings to execute that emotion. It may not be considered high brow, but it’s as balletic as anything else.

When discussing a movie that’s a couple decades old, baggage often follows—be it nostalgia, shifts in audience sensibilities, or just good old fashioned evolution—it’s there. Fresh air becomes stale over time and with movies, it’s a progressive art form that keeps feeding on itself. Someone watching this movie for the first time today may find it tame or a little lackluster, having spent the last decade imbibing modern classics like John Wick and Fury Road. However, I humbly request that if you’ve never seen DESPERADO, give it a spin. The technical acumen rides shotgun to the earnest conviction and passion on both sides of the camera.